INTRODUCTION

Successful companies, regardless of their industry or market, share one important thing – they know how to engage customers in a way that increases loyalty, share of wallet and profitability. They accomplish this in various ways – in-person, through various touch-points and online. With the proliferation of social media, mobile offerings and data-driven applications, the options for companies to engage with customers and prospects is increasing at a dramatic pace.

However, to successfully engage customers, you must have insight into the motivations and resulting behaviours of those people. And, when trying to build a successful online presence, the difficulties of trying to understand and predict human behaviour becomes even more challenging. Rarely do you have the benefit of being able to hold daily conversations with your customers to guide your decisions and finetune your offers. Split testing, metrics and user testing are all extremely important to any successful engagement strategy, but these techniques take time and in some cases, can be expensive.

Fortunately, some answers lie in the study of behavioural economics. According to Gallup®, this emerging discipline “can help business leaders and executives make sense of the economic behavior of real people and serve as a platform for effective management solutions. This is because behavioral economics complements traditional economic theory by filling in the gaps left by the realities of human nature.”

The premise of behavioural economics is: people are irrational, but predictably so. If everyone was perfectly rational, we would always act in a way

to give us the highest payoff. But because we are human and have human “defects” (we care about fairness and reciprocation, we follow the herd, we take shortcuts, etc.), we don’t always make the best decisions from a cost-benefit standpoint. By being aware of these idiosyncrasies, we can account for this apparently irrational behaviour and predict what customers might do.

This eBook provides practical advice for incorporating some aspects of behavioural economics into your online business strategy.

Part 1:

Fairness and Reciprocity:

4 Tips to Improve Customers’ Perception of Your Business

When we were young and dependent on our parents for money, my friends and I would “go Dutch” every time we went out to eat. Years later, one of my friends got his first job. With his first pay cheque, he picked up the entire bill at one of our outings. He didn’t know it at the time, but he started something in our group. As each of us made our way into the workforce, got a raise or changed jobs, we would take our friends out for a celebration.

This illustrates the concept of fairness and reciprocity. It was fair to cover our own expenses. But we reciprocated when we were shown generosity. The idea that we respond to each other in kind influences all sorts of decisions that we make on a daily basis. How much we tip our servers, what we buy for our best friend’s wedding, holding the door for the person behind us or leaving a complaint on a company’s Facebook page.

Fairness and reciprocity aren’t necessarily a dialog between the same two parties. For us to react appropriately, however, the action and its effort must be visible to us. Dan Ariely relays a story about a locksmith. As an apprentice, the locksmith took a long time to pick locks and often broke them in the process. But his customers happily paid him and even tipped him for his troubles. As he got better, he picked the locks faster and left the locks unbroken. He expected his customers to be even happier; however, the opposite happened – his patrons became less appreciative and stopped tipping. In effect, they rewarded effort but punished expertise. More often than not, we’re unsure of what a product or service is worth so we fall back on metrics that we can observe such as perceived effort or time and materials.

So what does this mean for your business?

• What am I getting out of it?

When you ask your customers for information, such as their email address, make it clear what you’re offering in return. For example, instruct your customer service representatives to ask “What’s your email address so that we can send you a coupon for 25% off your next purchase?.” Similarly if you’re trying to convince users to sign up for your newsletter, show them previous newsletters.

• Give away free content.

Consider offering value upfront, and let your customers reciprocate. This is how a lot of online communities work. Take, Stackexchange, a self-governing platform for questions and answers. Developers go there to get help from other developers. When their questions are answered, they are more likely to answer someone else’s question.

• It’s your turn.

Your customers have already given you their time and attention. In return, they expect you to solve their problems. Find out what their pain points are and reward them for their efforts. And if your customers have already given

you money, make sure you deliver on your end of the transaction. If they feel wronged, they may respond in a way that mirrors their negative experience.

• Be transparent!

It’s hard for people to value something abstract such as a service. In business environments where a lot of the value happens behind the scenes, show your process and give visibility to the hard work that goes into it. Here at Intelliware, we often give our clients a tour of the office, and we help them understand and embrace our Agile process. We show them how we prioritize index cards and post them in our project rooms to determine how we build incremental functionality. Because software development is such an abstract endeavor, these practices allow us to cut long feedback cycles and work in productive rhythm (reciprocity).

Finally, I’d like to leave you with an inspiring story from rhoner, a user from the online community, Reddit. He recalled a time he was stuck on the road due to a blown out rear tire. Many cars passed by in the four hours that he was by the side of the road. Finally, a man stopped with his family of six. He knew very little English, but went above and beyond to help. When rhoner tried to offer him money for his trouble, he refused. Struggling with the words, he parted with: “Today you… tomorrow me.”

Part 2:

Fairness and Reciprocity:

4 Tips to Drive Better Decision-Making

I’m fortunate enough to live very close to work. Most days, I walk to and from my office. However, on the rare occasions that I take public transit, I often wait much longer at the bus stop than it would have taken me to walk the distance. The longer I wait, the less likely I am to start walking.

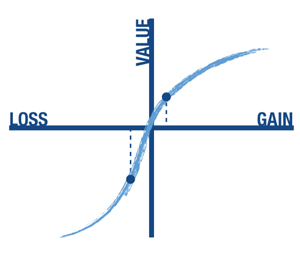

This sort of behaviour makes very little sense if you think about it, but we make these decisions over and over again in our lives: staying in an unfulfilling job, holding a bad investment, or postponing a doctor’s appointment. Our inability to walk away or change our course of action can be attributed to a theory called loss aversion.

Loss aversion states that human beings have a strong preference for avoiding losses over acquiring gains. In other words, we hate losing things a lot more than we like getting new things. In the earlier example, I know I can’t get back the time I’ve already lost – it is a sunk cost but I can save time if I begin walking. Yet I chose to wait.

At Intelliware, many of our clients come to us after they’ve sunk a lot of money into an off-the-shelf product that doesn’t work for their business. That decision is hard, and deserves to be recognized. It means acknowledging the loss (the cost of the product, as well as the time and effort that went into it) and evaluating new options independent of past investments—in this case: custom software development.

Loss aversion also explains why the Agile process works so well. Delivering value early and often encourages us to constantly validate that we’re heading in the right direction because even the smallest loss causes us to respond in surprising ways.

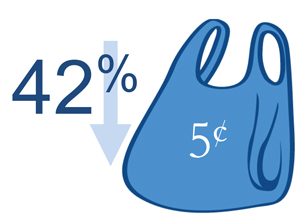

For example, take this natural experiment in the United States. In 2012, Montgomery County introduced a five cent tax on grocery bags and experienced a 42% decrease in the use of grocery bags. Meanwhile, store chains in the Washington Metropolitan Area offered a five cent incentive on reusable grocery bags, but saw no change in consumer behaviour.

Now that you understand how this quality governs a lot of our daily decisions, what does this mean for your business?

• Give out promotions.

Instead of making your customers buy a product outright, consider giving

them a free trial or a promotional price. Of course, the product itself must be compelling. Having it brings joy, and losing it would be awful. Furthermore, continuing the trial justifies the time and effort a user would have already invested into the product. The idea of losing out on a great deal is much stronger than getting the discount itself.

• Re-think incentives.

A common engagement technique in gamification is rewarding the user for actions and achievements. These digital tokens can be points or badges. The theory is that the user will actively seek these rewards and therefore engage with the application more. A potentially more addicting strategy would be to give out the reward first. Then, if the user fails to accomplish some task within a certain timeframe, he runs the risk of losing it.

• Use effective copy.

Think about how you word your value proposition so it can be framed as either a gain or a loss. For example, “Save time with our expense tracking software” vs. “How much time are you wasting filing expenses by hand?” On one hand, you’re asking your customers to evaluate something they’ve yet to gain. In the latter, your customers are reflecting on time they’ve already lost. The emotion of loss will drive them towards action.

• Defer registration.

When possible, defer registration until the user has already invested some time with you. For example, enable them to complete activities until they need to save their work. At that point, walking away would mean losing that investment. Rearrange a form so the comment field is first and the name and email fields are placed last. Or, allow your customers to apply for a quote and give them the opportunity to save it. The rationale is giving them the opportunity to sign up to not to lose the work they’ve already done, as opposed to evaluate what they can gain by signing up. This also works because of fairness and reciprocity: giving your customers value before asking for information in return.

As a final takeaway, evaluate your own decision-making. Are you sacrificing opportunities because of sunk costs? Are you taking calculated risks? Overcome loss aversion by identifying what it is that you’re scared of, and make a move forward. Shift loss aversion to the goal you can’t afford not to attain.

As a final takeaway, evaluate your own decision-making. Are you sacrificing opportunities because of sunk costs? Are you taking calculated risks? Overcome loss aversion by identifying what it is that you’re scared of, and make a move forward. Shift loss aversion to the goal you can’t afford not to attain.

Part 3:

Choice Architecture:

The 4 Decision-Making Shortcuts

Organizing dinner amongst friends is stressful. The most difficult decision is always the venue despite everyone’s indifference. Neither the organizer nor the guests want to be responsible for an evening of bad food or service by suggesting a location. Limiting the choices to a few restaurants helps but doesn’t generally bring the party any closer to a decision. The most effective strategy is to pick a default venue (by proximity, rating or personal preference) and invite guests to make other suggestions. Indecision by the guests is now an acceptable option and it absolves the organizer from the weight of their recommendation.

Business owners face variations of the same dilemma, though the consequences of a bad decision are often more severe than a bad dinner with friends. With multiple stakeholders and even more options, the decision-making process is often drawn-out and deliberate. What we don’t realize is that despite our best efforts to be methodical, sometimes our actions are influenced by factors we aren’t even aware of. Our minds take decision-making shortcuts.

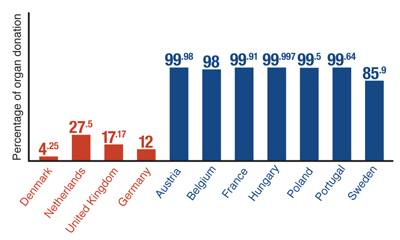

One of the most powerful shortcuts we use is accepting the default option when things get complicated. In a paper published in 2003, Eric J. Johnson and Daniel G. Goldstein observed a dramatic disparity in the rate of organ donation between various European countries.

Source: Defaults and Donation Decisions

The staggering discrepancy between these European countries is the result of one small difference in their Department of Motor Vehicle’s forms: “Check this box if you want to be in the organ donation program.” When this box was checked by default (i.e. in the blue countries), 85-99% of citizens were willing to donate their organs. When this box was unchecked by default (i.e. the red countries), only 4-27% were willing to donate their organs.

Two conclusions were drawn from this study:

1. When decisions are hard and complex, we don’t make any choice at all. This may be the result of loss aversion, wherein the fear of choosing the wrong option, thus incurring loss, causes indecision. Under these circumstances, we fall back on simplifying strategies. We take the path of least resistance and accept the default option; we look to an authority for guidance; or we take cues from past experiences or social norms.

2. The meaning we assign to the choice is influenced by the default option. When participants are asked to opt-in, the decision is seen as more important. Conversely, decisions where participants have to opt-out are perceived as less significant. Going back to the organ donation example, another related study surveyed the citizens of each country and found that the countries that employ an opt-in policy see the decision akin to donating 20% of their annual salary to charity. In contrast, countries that use an opt-out policy perceive it to be similar to giving 2% of their annual income to charity.

It is unsettling to believe our choices, and even our values, are influenced by the design of a form. We like to perceive ourselves as having independent thoughts and known preferences. Given complete information, we have the capacity and the freedom to make the best decision. And yet, human idiosyncrasies consistently reveal themselves in our actions through both trivial (e.g. dinner) and complex (e.g. organ donation) decisions.

Choice architecture describes how decisions can be influenced by the way the questions and answers are presented. Selecting the default option is a transparent technique in guiding behaviour. More subtle influences include ordering, anchoring or narrowing the selection.

How can understanding these biases help your business?

• Define the default.

Create the path of least resistance by preselecting a default. This could mean leaving the subscription checkbox selected or highlighting the most common option in the pricing table. Conversely, if you want the consumer to think twice, require them to take an explicit action before they can proceed such as agreeing to the terms of service or adding a confirmation or preview state. Defaults through selection are explicit whereas making a recommendation is suggesting a default implicitly.

• Ordering matters.

In situations where the customer has no strong preference, or doesn’t know enough about the problem to choose, people tend to select the middle option in an ordered list. It is the safest choice amongst each extreme, thus minimizing risk if they’ve made the wrong decision. For example, if consumers have the option of three packages with varying features, they are more likely to select the middle option because they aren’t yet aware of which option is best for them.

• Anchoring.

We compare in relative terms. Without knowing the true value of something, we compare it to past experiences or similar things. When listing products, consider ordering them from most expensive to least expensive. Items following the first product will seem cheap in comparison. Or, if you’re going to ask someone to value something abstract, establish an anchor like leaving a $20 dollar bill to seed a tip jar or suggesting a donation amount.

• Narrowing the selection.

When there are too many options to process, consumers encounter the paradox of choice and the options are paralyzing. Take away that anxiety by creating subsets that are more manageable. Just as a default is selected amongst a few, a subset can be selected amongst many. For example, the 10 most popular items, staff picks or a monthly promotion.

You may also consider using a combination of these techniques. This is the case with popular SaaS company, SlideShare. It defined its “default” state by highlighting their most popular option, the Silver package, out of its four offerings. It’s the safest choice, and it’s backed by social proof.

These shortcuts help us make decisions quickly so we can free up our attention for more important things. While it’s easy to see the consequences of a bad choice, we don’t often recognize the cost of indecision.

Additional resources

http://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2011/04/how-shortcut-decisionstrategies-affect-decision-outcomes.phphttp://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/publications/observer/2012/j anuary-12/the-mechanics-of-choice.html

http://www.pnas.org/content/109/38/15201.full http://www.ted.com/talks/barry_schwartz_on_the_paradox_of_choice.html

http://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2011/03/how-anchoring-orderingframing-and-loss-aversion-affect-decision-making.php

Part 4:

Herding:

3 Tips for Influencing Others

There are a lot of food options around downtown Toronto.

We have the choice of exploring the PATH (the retail-laden tunnels that link the office buildings underground), strolling down Queen Street, venturing to King West, or settling in at any number of restaurants along Adelaide. Yet, inexplicably, there’s always a line at my favourite places while others remain unloved.

A number of different reasons may be responsible for why a handful of restaurants are so popular. Perhaps it’s because we aren’t very adventurous; an old favourite is hard-pressed to disappoint us. Or, after a morning of calculated decisions, autopilot carries us to our default lunch spot before it even registers. Alternatively, because we’ve been there before and had a good time, we want to experience it again. When we get tired of the old standbys, it’s difficult to convince ourselves to try something new when the restaurant is empty unless someone vouches for it. So we find ourselves joining the line of an already busy establishment. Loss aversion pushes us to make safe choices, and we rely on defaults when we’re indecisive or indifferent. Today, I want to focus on the last behaviour mentioned – joining the line of an already busy establishment.

• The notion of following our past behaviour is called self-herding, a concept defined by professor Dan Ariely of Psychology and Behaviour Economics at Duke University. If we do it once, we are likely to do it again. In the example above, we continue to be patrons of a restaurant that provides a good experience. This is how habits are formed.

• More generally, herding refers to following a gathering, like waiting at an already crowded venue. It’s a basic signal of social proof: evidence of appropriate behaviour as illustrated by others. For example, with so many people in line, a restaurant must be good. Or standing outside an unlocked door with a group of people under the assumption that someone must have tried opening it already. The more we can relate to the people around us in those situations, the stronger the social influence.

Vouchfor!™ is a venture Intelliware worked with to leverage the exact premise of social proof. A good reputation and positive reviews are considerations in the purchase cycle; however, recommendations from friends or people you trust carry a lot more weight.

Vouchfor! allows merchants to manage referral campaigns, offering incentives and tracking customers and their referrals. This is built upon what people are already doing freely: vouching for contractors, agents, restaurants and other businesses. Recognizing this, the service hoped to encourage and amplify that behaviour through incentives and create a self-herding habit; when a friend needs X, an existing customer will recommend Y. Done often enough, Y will be associated with X.

It’s worth noting that large scale behavioural change may begin with self-herding if it garners enough momentum, sometimes even self-generating. For example, let’s say you learn your neighbour’s energy spending is lower

than yours (social proof). You and your neighbour are pretty similar so it causes you to re-evaluate your energy consumption. You get used to turning off the lights when you leave the room and limiting the use of the air conditioner (self-herding). People across the street hear about this and consequently reduce their usage as well. Once this reaches a critical mass, lower average energy expenditure becomes the norm. Deviating from this average will paint a household in a negative light (social pressure).

The next time you try to persuade customers or prospects, consider the techniques of self-herding and social influence:

1. Use testimonials, reviews and ratings.

We equate testimonials, reviews and ratings with evidence that someone else has tried the product or service. Actions that require little effort, such as a rating or clicking “Like” on Facebook, are easy for people to do; however, on the receiving end, we give reviews and testimonials much more weight. The more personal the channel of communication, the better. For example, broadcasting a Twitter endorsement is less effective than sending a friend a text message about the same business. Facebook highlights friends before strangers in events listings to be persuasive. Marketing emails that address customers by name are better received.

2. Create a virtual line.

Consider using a waiting list as a signal for value and scarcity. For events, display the actual waitlist or RSVPs. Before a product is launched, establish a pool of beta users. Mailbox manoeuvred a brilliant user experience that resulted in an 800,000 person waitlist. By displaying the current number of people in line, it created anticipation and exhibited social proof. After all, why would so many people wait if it wasn’t worthwhile? By displaying your place in line, particularly the number of people in front and behind you, the app illustrated progress and created artificial status.

3. Use a loyalty program to establish a relationship.

If I am loyal to a business, the business should be loyal to me. It’s the basic principle of fairness and reciprocity. The goal is to create a series of good experiences to keep customers coming back. It reassures them that they are making a good choice each time. A collective history of good experiences from many different people enables you to build a credible brand which, in turn, others will follow.

Self-herding and following social norms are shortcuts we take when making decisions. However, it’s important that we’re aware of when we’re using these biases. If we follow a crowd blindly, we may draw the wrong conclusions for ourselves. There is a reason your mom used to ask, “If your friend jumped off a bridge, would you do it too?” If we don’t pay attention to the history of our own actions, we risk developing bad habits.

Additional resources

http://oliversycamore71.wordpress.com/tag/self-herding/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LY0550isFXg

http://www.ted.com/talks/alex_laskey_how_behavioral_science_can_lower _your_energy_bill.html

http://www.cbsm.com/cases/using+social+norms+to+reduce+household+e nergy+consumption_170

http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/news/releases/energy-usestudy-demonstrates-power-of-social-norms.html

Part 5:

The Empathy Gap:

3 Tips to Help You Emotionally Connect With Your Customers

Intelliware put together an Ultimate Frisbee team this summer. We didn’t win very often, but we were a spirited team. Our players traveled back downtown from all over the city for our late night games and even brought their children to cheer us on in the rain. But despite giving it our best shot, the sport wasn’t kind to us. Between pulled muscles and sprained ankles; half our team was injured by season’s end.

The social proof was in the casualties. I should have warmed up, used a brace or stopped altogether, but my new found love for the sport kept me running. Before the season began, I chastised a friend for being too zealous and injuring herself in her Monday night league. After our final game, I found myself in the same position, limping to the office. When we make a lapse in judgment, we’re often hard on ourselves. This is because the decisions we consider “foolish” after the fact are often the same decisions we believe are rational at the time we make them. We know better. Other scenarios in this category include grocery shopping on an empty stomach, not saving for the future, or drinking and driving.

The misunderstanding between what we ought to do and what we actually do may be the result of the hot-cold empathy gap. Coined by psychologist George Loewenstein of Carnegie Mellon University, the hot-cold empathy gap explores the idea that human beings cannot accurately predict active or “hot” behaviours in a calm or “cold” state. Hot influences, often visceral in nature, include love, pain, lust, hunger, fear or fatigue, and we constantly underestimate the impact these influencers have on our actions.

In software development, clients tend to underestimate the effort it takes to practice Agile development. Having experienced the shortcomings of traditional methodologies, the Agile approach makes a lot of sense when it’s proposed and contracts are signed in good faith (the cold state). But when requirements change as we engage actual users, it becomes extremely tempting to fall back on the familiar activities of a more traditional waterfall approach. Deviance from the original plan introduces risks that put us in the hot state of uncertainty and it becomes harder to remember that adapting to change is one of the main ways that Agile development helps us build better software.

Knowing that we can be governed by emotions rather than logic, how can we make better decisions? How can we empathize with our customers or even help our customers empathize with us?

1. Close the gap.

If you’re trying to persuade a customer to make a decision now for the future, try to replicate the conditions of their future state. For example, if you’re trying to convince your customers to install new windows, approach them on a cold day. Playspent.org has developed a web-based game to close the gap. The game simulates a series of unfortunate events that may cause you to require social assistance. At the end of the simulation, it asks the user to donate a small amount to help those in need.

2. Tell a story.

Numbers and statistics provide a sense of scale; however, when you want to elicit empathy from your customers, it’s more effective to use case studies because they tell a story. Position your customer as the main character who solves a problem with your help. As you’re crafting your story, remember the following advice from renowned marketer, Seth Godin: “Stories don’t always appeal to logic, but they often appeal to our senses.” Consequently, creating customer personas helps tell stories, especially when real photos and quotes are used. They help stakeholders create an authentic connection with their end-users.

3. Stop yourself.

If you know that you’ll be putting yourself in a position where your judgment might be impaired, account for it in advance. Keep junk food out of your home to avoid eating unhealthily. Leave your keys with a designated driver if you plan to drink. Seek a neutral, third party to test your software before you release it.

The empathy gap not only affects our decisions, but it is also the way in which we interact with one another. Remember that our decisions are affected by both logic and emotion. We must remember not to judge others, such as our customers and users, too harshly when they behave unexpectedly. If you can be patient in these situations, you’ll forge stronger relationships because of it.

About the Author

Veronica Wong

Usability Specialist, Information Architect and Software Engineer with a proven history of delivering design interfaces that are delightful, friendly and user-centered. Veronica provides creative solutions throughout the design and development process, from delivering use cases, storyboards, information architecture and site maps to designing wireframes, prototypes, websites and applications. She has a keen interest in Behavioural Economics.

About Intelliware Development Inc.

Intelliware is a custom software, mobile solutions and product development company headquartered in Toronto, Canada. Intelliware is a leader in Agile software development practices which ensure the delivery of timely high quality solutions for clients. Intelliware is engaged as a technical partner by a wide range of national and global organizations in sectors that span Financial Services, Healthcare, ICT, Retail, Manufacturing and Government.