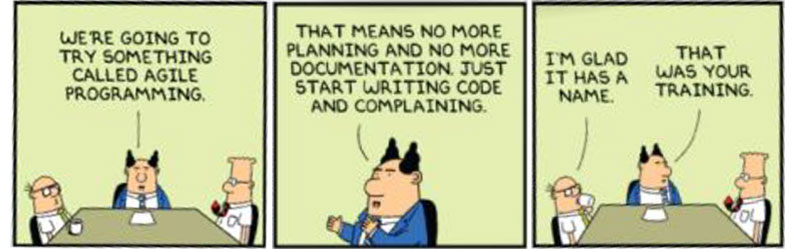

Once primarily the domain of early adopters, Agile flavoured methodologies have steadily gained acceptance as a mainstream approach to software development.1,2,3 Although Agile has come to mean many different things to different people, at its core, it is a philosophy that guides a set of technically rigorous development practices. It has been adopted by a growing number of organizations to lower the risk that is inherent in software development and to deliver better software as defined by the end user. As more teams adopt Agile practices and more companies transform to Agile cultures, we continue to learn together about the best practices and benefits of developing software in an Agile manner.

This introductory paper is designed to provide a basic understanding of Agile software development.